Early Education Is a Game Changer: New Report Shows That Reaching Infants and Toddlers Reduces Special Education Placement, Leads to Soaring Graduation Rates

Photo: American Educational Research Association

Photo: American Educational Research Association

Access to early-childhood education significantly reduces students’ chances of being placed in special education or held back in school and increases their prospects of graduating high school, according to new researchpublished by the American Educational Research Association. The report synthesizes evidence of the lasting, long-term benefits of high-quality preschool programs, which have often been dismissed as transient.

Authors from Harvard, New York University, the University of California, the University of Washington, and the University of Wisconsin contributed to the brief, a meta-analysis of 22 experimental early-childhood-education studies conducted between 1960 and 2016. Although previous research reviews had focused on programs targeting 3- and 4-year-olds, the AERA brief examined services offered to children between birth and age 5.

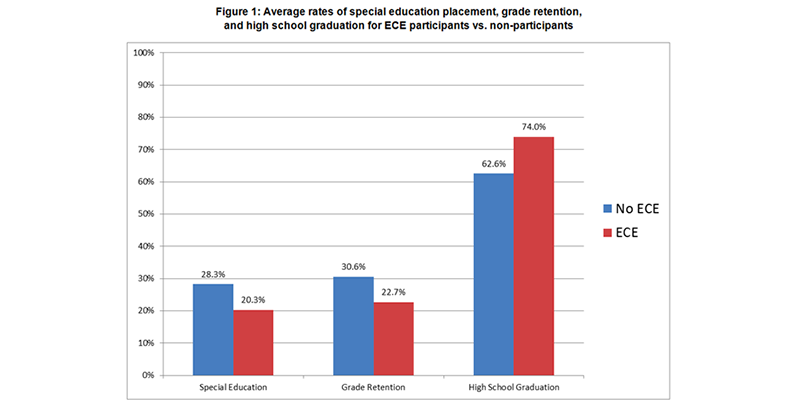

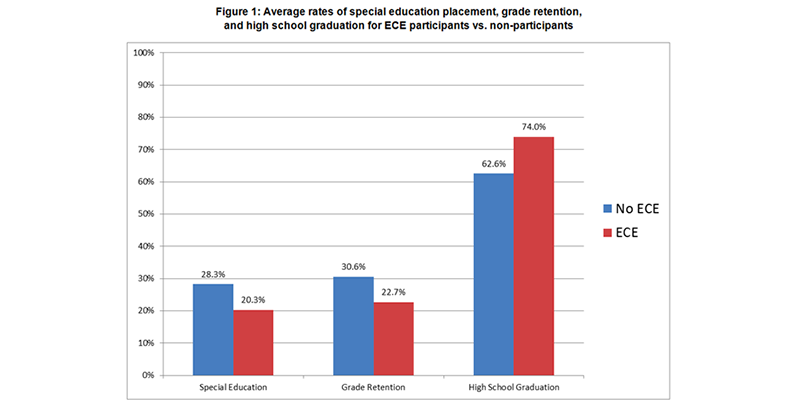

The results were impressive: The programs reduced subsequent special education placement for participating students by 8.1 percentage points, reduced the chances of being held back by 8.3 percentage points, and boosted high school graduation by 11.4 percentage points. Though high-quality preschool is generally thought to accelerate cognitive and language development in the near term, the researchers conclude that its effects can be detected as late as high school.

(Photo: American Educational Research Association)

“These results suggest that classroom-based ECE programs for children under five can lead to significant and substantial decreases in special education placement and grade retention and increases in high school graduation rates,” they write.

Tallying the financial blow of children’s academic struggles, the brief presents a case for greater public investment in early education. The estimated cost of placing a student in special education classes is roughly $8,000, and holding a student back a grade costs about $12,000, according to the report. Meanwhile, each of the 373,000 American high schoolers who drop out each year earn almost $700,000 less over the course of their careers than peers with diplomas.

Although providing excellent preschool programs to the millions of children currently without them is an expensive proposition, economists have recently argued that later-life payoffs — better health, lower rates of incarceration, and higher earnings for participants — justify the costs many times over. In a study of two of the oldest and most famous preschool experiments, the Carolina Abecedarian Project and the Carolina Approach to Responsive Education, Nobel Prize–winning economist James Heckman estimated that the programs yielded $7.30 of benefit for each dollar spent.

Yet even as states have contributed millions of dollars in new spending on preschool systems, skeptics like the Brookings Institution’s Russ Whitehurst believe that the impact of the programs is unlikely to be retained once they are scaled up to serve millions more children.

Others have pointed to evidence of “fadeout,” a phenomenon by which the positive impacts of preschool dissipate in the years following completion. One Michigan lawmaker, whose nomination to a post in the Department of Education was withdrawn after a cache of his old blog posts were criticized, denounced the federal Head Start early childhood initiative as “a sham program” this month.

“There have been a number of independent studies over the years that have concluded that these program children come to school with no more social or cognitive abilities than their non-program counterparts,” he wrote in one post. “So why then do we continue to pay for this failure?”

But the authors conclude that nearly 60 years of experimental studies indicate clear results from such programs that last into at least adolescence.

In fact, the effects on special education and retention were found to be greater when researchers followed up years later than they were at the end of the early-childhood programs in question.